Heinrich Mutter

Vita

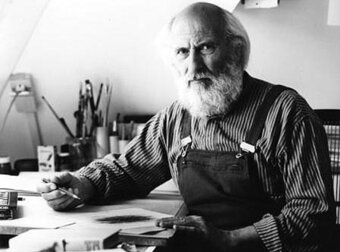

Heinrich Mutter in his studio, 1995

The drawings by Heinrich Mutter in the Heart Center raise a fundamental question: How did the artist arrive at his abstract compositions? An artist born in 1924 is unlikely to have painted or drawn non-objectively from the outset. So what came before, and how did his artistic path unfold?

A look at earlier watercolors reveals a bold spectrum of developmental variants and, even more, the sudden leap into abstraction. But was this really a leap and not rather a consequence of his "ars inveniendi et investigandi", the art of finding and inventing?

One of the first stations in Mutter's artistic maturation process was the Swiss painter and sculptor Walter Bodmer, who had been a teacher at the Basel School of Applied Arts since 1939. In 1946, the 22-year-old, who had just escaped the war and been released from captivity, seized the opportunity to be trained by Bodmer in Basel - a decisive step on his artistic path, as his teacher saw art as a universal tool for making sense of the world: "I painted whatever came before my eyes: landscapes, figure paintings, bullfights, artists and also figurative compositions".

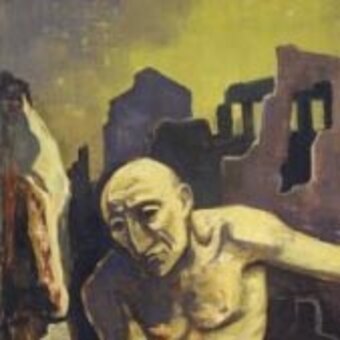

Bodmer's compositions, here one from 1956, must have fascinated Mutter the most.

Mutter immersed herself in this world, which can also be seen in the watercolors in terms of composition: landscapes, figure paintings ... but also compositions. It is probable that her artistic path began in this year, but it cannot be determined exactly. Earlier events or encounters could also come into question, such as the 17-year-old's apprenticeship as a painter or his enthusiasm for Max Slevogt's "Leatherstocking Illustrations". However, such stages in a young man's life should not necessarily be accorded overture status for an artistic career, especially as the Lederstrumpf stories have an experiential potential that makes Slevogt's lithographs seem secondary.

Or was it simply an addiction to looking at pictures? The picture that says more than the text, develops more atmosphere than the spoken word and begins to speak to you in silence, in a kind of silent dialog? According to contemporary Wolfgang Heidenreich, Mutter looked at pictures by Karl Hofer while he was painting in a factory owner's villa in Bad Säckingen. That robbed him of his sleep. So it was Slevogt after all and not Lederstrumpf!

But what might have fascinated him about Hofer? Perhaps it was the artistic reduction of the human figure to structures and color forms. In other words, it is about the image, about the reality of color and form, but no longer about the outside, which must be depicted as realistically as possible. It should also be borne in mind that the abstracts that were ostracized during the Third Reich were not immediately available after 1945. Reduction and abstraction or the reality of color and form had been thought of, but there was a lack of visualization. Bodmer's idea of "figurative composition" could of course have been a tremendous impetus for artistic experimentation, as "I painted what came before my eyes" strikingly emphasized, if not explicitly demanded, the freedom of artistic creation, and Bodmer provided the visual material for his artistic credo.

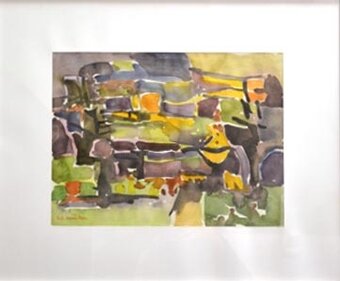

To what extent was this arc of tension from Karl Hofer to Walter Bodmer, with its focus on the artistic reduction of the real, momentous for Heinrich Mutter? Two watercolors from 1960 illustrate a rapid artistic development. Two landscape sections with rock formations, which are rather vaguely recognizable as such, mark a path from the expressionist Hofer to the "semi-abstract picture". What does this mean? Mutter learned the method of reduction from Hofer. He frees the concrete landscape from the "realia" until he arrives at the basic forms, which in turn convey conclusions about "landscape".

This balancing act between concretion and abstraction opens up an aesthetic field of tension that Paul Cézanne and, a little later, the Cubists masterfully staged before him and that important contemporaries of Mutter also presented. This gave rise to the Southwest German School of the decades after 45, with its centers of influence in Karlsruhe and Stuttgart: Otto Laible, Fritz Steißlinger, Maria Caspar-Filser, Peter Jakob Schober and Herrmann Stenner. However, many of these artists stuck to "semi-abstract" paintings and only a few, such as Theodor Werner, aimed for non-objective compositions. This was also the case for Heinrich Mutter, for whom this balancing act was merely a step towards his own abstract painting. He may even have realized at the time that the subjective experience of a landscape does not produce its reality content, but rather an idea of the landscape that is not compatible with the given forms, the realia. This called for the construction of his own reality, which corresponded to his ideas and the moods they contained.Bodmer's delicate compositions continued to populate his artistic landscape of longing.

However, it was not easy to let go of the stage he had reached, as Mutter's compositions were not only appealing but also promising. He suddenly finds himself standing alongside the greats of southwest Germany. This is a confirmation of his work to date. Why should we break away from this? Many watercolors from the late sixties and early seventies illustrate this oscillation between abstraction and concretion and prove the inner struggle to break away from the highly praised.

The pure color composition (watercolor from 1971) repeatedly tilts back into figuration, as if this and only this is able to give the picture stability.

Buildings grow out of elegant color interlacing (watercolor from 1969) ...

... or a massive rock suggests a bay (watercolor from 1970), although the coastal landscape itself is dissolved into grid-like color patterns. This was probably what prevented him from leaving the aforementioned ridge and taking the decisive step into abstraction. Perhaps he also did not want to miss the applause of the public.

From a technical point of view, he probably also doubted whether a reduction of the reduced form was possible. So he reviewed the compositions of his paintings and considered different sections. He may have identified many other watercolors in one watercolor ...

... and picked out one or the other pictorial element to modify its form, as in a watercolor from 1993.

This was a lengthy process, as evidenced by the fact that both watercolors were created more than twenty years apart. But then came the decisive step towards abstract composition, which already points in the direction of the drawings from the nineties, as the watercolors from 1994 and 1995 illustrate.

This artistic process can probably only be compared to Piet Mondrian's famous "Apple Tree Metamorphosis" from around 1915. He "extracted" the structure of an apple tree from the trunk, branches and foliage and presented it as a composition that had to be "straightened" so that he finally arrived at his colorful and large-scale grid pattern. Wassily Kandinsky, whose later compositions grew out of concrete pictorial worlds, also undertook a comparable "pictorial transformation".

The artistic significance of Heinrich Mutter's drawings in the corridors of the Heart Center can only be assessed in the context of his earlier work. The genesis of their creation transforms them - but only in the mind of the viewer. Or to put it another way: knowledge of the early watercolors could lead to the discovery of hidden landscapes in the late drawings. What a fascinating perspective!