Erwin Wortelkamp

VitaBorn in Hamm/Sieg in 1938, Erwin Wortelkamp studied sculpture and art education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich under Professor Robert Jacobsen from 1960 to 1965. After working as an art teacher, he was offered a position as a lecturer at the University of Education in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1973. In 1975 he settled in the old schoolhouse in Hasselbach, then resigned as an assistant in 1980 and began the fascinating project "im TAL" in 1986. This involved the sculptural design of a landscape garden, in which over 30 colleagues took part. The project is still being continued today on an enlarged site of 10 hectares. It was, and still is, about the interplay between art and nature. There is a fundamental question at the heart of this: is a sculpture made for a landscape situation any different from a museum object? Basically not, as the design interests are in the foreground. It is therefore a question of searching for and finding a specific form that is appropriate to the sensory experience.

For Wortelkamp, it is the wood that needs to be worked. Here he first finds his own growth of form, which he wants to present, parallel to nature, as an artistic natural object or natural-like art object - whatever it may be. The artist himself sees this process of creation in a much more differentiated way.

"For me, the keyword is 'being on the move', the processual. Art also intervenes in the processual becoming of the individual. Art embodies what has happened as a display. Art is a process halted and stopped by the artist, a pictorial whole that would otherwise not exist. We can encounter this pictorial whole, based on our developed perceptive faculties. Sensory training - that would be an important prerequisite for being on the move.

"These thoughts go to the heart of Schelling's theory of art, meaning the "double thesis of art". More importantly, Wortelkamp's reflections go beyond this. For Schelling, nature presented itself as a process that cannot be imitated by art, as the latter represents a static principle. And art, according to Schelling, is also incapable of visualizing the process of nature. Wortelkamp's idea of the "stopped process" captures the facts: the work of art begins with the process of finding and shaping and thus corresponds to the essence of nature. The traces of the process can be read in the presentation of the object - but only because the process has been stopped.

Being on the move is the agent of the artist, who sees himself as part of the natural process. The transcendent side of these thoughts may slide onto the religious level. In 2002, Wortelkamp erected a cross in the nave of Bamberg Cathedral, in the Carmelite monastery he leaned a stele entitled "Magdeburger Rote" against the wall or a "Hand", which he placed in an empty niche for figures in the choir of Bamberg Cathedral. The sculptures only seem strange because our perception is not calibrated to these combinations. But if you linger for a while, you can sense that there is an intimate and natural relationship between the object and the space. This juxtaposition of free design and built space encourages meditation and allows the sacred to be experienced. The viewer also undergoes a process. They perceive themselves when looking at the sculpture, find their place and feel like an aesthetic partner of the ensemble: the whole is always more than the sum of its parts. With his creative work, or better still, with his artistic ability to find the "right place" in order to stage sculpture-architecture combinations in the urban or interior environment, Wortelkamp paved the way for the sensual experience of our living space. Being on the move thus refers not only to the process of design, but also to the choice of location and, most importantly, to the art of combination. In the peculiar atmosphere of Wortelkamp's works, being on the move is encoded. The viewer experiences this aesthetic process as a wonderful and revealing experience for his own perceptive faculty.

Wortelkamp has a lot to say. Opportunities presented themselves to him as a visiting professor at the universities in Giessen (1982-83) and in Witten/Herdecke (1995-96). For him, the combination of theoretical considerations and artistic processes takes place in the visual arts.

Wortelkamp: "Every artist arrives at a form-finding process that can assert itself in a condensed complexity in the most diverse contexts. These newly emerging contexts are co-determined by the respective surroundings and always by the eye of the observer."

It is rare that a theoretical statement is compatible with practical implementation: Bamberg 2002 "Skulpturen finden ihren Ort". Wortelkamp set up his sculptures at various locations in the city in order to create new aesthetic perspectives. The result was a pattern of dialog that the viewer could not escape. The dialogical principle unfolded between sculpture and architecture, which irritated pedestrians as a "new unit" and challenged them to react in whatever way. It is possible that the viewer will isolate the sculpture and either approve or reject it as an aesthetic object in its own right. But it is also possible that the sculpture gives him a new approach to architecture.Wortelkamp's concept of art is broad and goes beyond traditional definitions and hypotheses. This is due to his resolute attitude of seeing himself as part of the natural process in his work. An impressive example may illustrate this: In April 2001, Wortelkamp came across the white willow uprooted by hurricane "Lothar" on the grounds of Schöntal Monastery. He worked on the uprooted tree for four months. The result was a stupendous sculptural landscape, which the artist christened "Lying". It was moved into the monastery church and then returned to the "site of the event". There it will enter into a dialog with its surroundings. The sacred atmosphere of the sacred space was carried into the outside world with the sculpture. When asked whether there was also something religious about nature, Wortelkamp replied:

"Just as perhaps all nature exists in us as a form of longing and seems difficult to grasp because it does not exist in this form."

With his work, Erwin Wortelkamp has opened a window to "nature as a form of longing".

Ehrenfried Kluckert

Head - for Gert von Briel, Bamberg, wood, Pfahlplätzchen, 1983

Socketed fragment, bronze, 1997/2002

In front of the Brückenrathaus in Bamberg

Hand, wood, 1998

Obere Pfarre (high choir), Bamberg

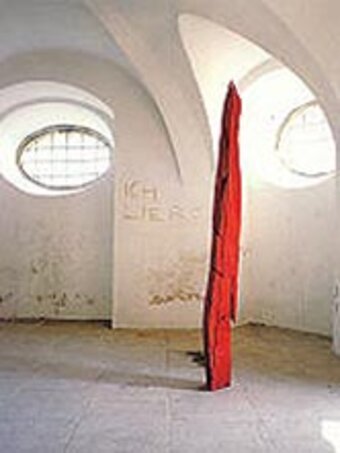

Red standing woman, wood, 1995

Kavaliershaus, Bamberg

Wall piece, wood, 1991

Erfurt, Michelsberger Straße 2-4

Stele, wood, 2002

Crematorium at the forest cemetery in Duisburg