Smoothing the emotional waves

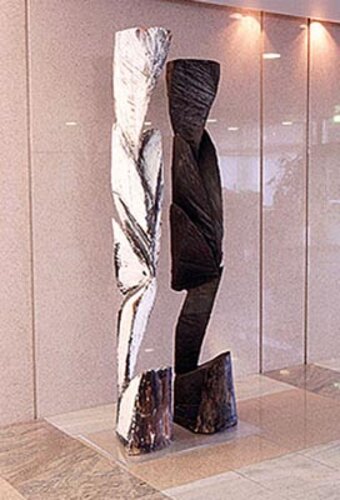

Ehrenfried KluckertA towering double figure watches over the hustle and bustle in the busy entrance hall of the Bad Krozingen Heart Center. The wooden sculpture designed by Karl Manfred Rennertz - a painted Douglas fir and a fire-blackened elm from 1999 - signals the clinic's artistic ambitions.

It all began in 1986: the "arrival of art" was celebrated with an exhibition of drawings by Gunther Vogel. A year earlier, curator Beate Hill-Kalusche had developed an exhibition concept together with the clinic's administrative director and a representative of the Professional Association of Visual Artists. The fact that a clinic is an unusual exhibition venue had to be taken into account. Gallery concepts of the usual kind could therefore not be transferred. On the other hand, the aim was not to install a pleasing "decoration system with art", but to present sophisticated avant-garde art. A "catchy" concept was agreed upon: artists from the southwest of Germany whose works were already being discussed in the public art scene were to be exhibited first. Furthermore, an academy degree or adequate training at an art school was obligatory.

In 1998, the opportunity arose to present the exhibition concept in Florence at an international congress organized by the Tuscan Ministry of Health and Culture and the Fondazione Michelucci in collaboration with UNESCO. The concept was included in a program of guidelines for art in hospitals. Over 60 exhibitions have been held to date, including in cooperation with museums in the region.

Karl-Manfred Rennertz, wooden sculpture welcomes the entrants

The "Art Room" of the Heart Center is divided into three areas: Paintings, drawings and wall objects are displayed on the attic floor. Larger sculptures and paintings in particular can be seen in the bright entrance hall. There are also three showcases here in which small sculptures attract attention. The clinic park offers space for extensive sculpture exhibitions.

Through regular purchases over the years, the clinic has succeeded in building up an interesting and varied collection, with works generously distributed throughout the entrance hall, dining room, waiting areas, corridors and offices.

In May and June of last year, an exhibition featuring the sculptor Gert Riel made a name for itself. Riel, who has had numerous exhibitions in Germany and abroad, set up his monumental iron steles in the park. His drawings - the "models" of his sculptural works, so to speak - were on display on the attic floor. In addition to the avant-garde artists, the curator selected the sculptor Kurt Lehmann, a representative of classical modernism, for the first exhibition this year. Born in Koblenz in 1905, the sculptor moved to Staufen, the neighboring town of Bad Krozingen, in the Markgräflerland region in 1970. He died in Hanover in 2000. The sculptor, who was awarded many important art prizes, is represented by small sculptures, a half-length figure and a large standing figure. The small sculptures in particular illustrate Lehmann's artistic ability to depict the human figure in changing motifs of movement.

A Lehmann sculpture in front of pictures by Erwin Wortelkamp in the entrance area

Parallel to the sculpture exhibition, the paintings of the young artist Heinz Thielen are currently on display on the Attika floor. Thielen, born in 1956, studied under K.R.H. Sonderburg at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart, among others. The contrast of monochrome rectangles and painterly structures irritates the eye. This is what makes the pictures so appealing. The viewer feels like the artist of a self-staged viewing process. The confrontation between the classic and the avant-garde artist creates a wide-ranging field of tension that encourages viewers to take a closer look and engage with the work.

While the lively entrance hall leaves little room for quiet meditation, the waiting area in the surgery, for example, offers peace and tranquillity for extensive contemplation. Renata Thong's paintings may be suitable for this, as her figurative compositions offer a broad spectrum of associations. The changing light and color conditions suggest a pictorial dynamic that sometimes turns abstract forms into representational patterns.

Patients, doctors and nursing staff like to visit a particularly attractive place in this part of the building, the oriel room at the back of the surgery. It not only offers a magnificent view of the park area, but also of the landscape painting by Jörg Hilfinger, which could not have found a better place in this "miniature Hermitage".

The spacious and light dining room is something like the social center of the clinic. This is where patients meet with their relatives and friends. The large-format works by Peter Stobbe dominate the room and have certainly often provoked intensive art discussions. His works often appear in combinations of images and challenge the viewer's imagination. They feel challenged to recognize references between pictorial objects and paintings in order to create an "overall composition" of the separate segments.

And the patients on their wards? They too can enjoy the art. The curator Hill-Kalusche has had an impressive collection of over 200 art prints from the period after 1945 distributed in the corridors and common areas.

A painting by Erwin Holl in the dining room

Healing and recovery are the highest goals of medical endeavor. But dying is also part of everyday hospital life.

In an emergency, the two hospital realities are often irreconcilable opposites for everyone involved. This results in difficult situations and questions for doctors and nurses, but also for relatives and the dying patients themselves. For this reason, nurses and an interdisciplinary committee of the clinic, including management, representatives of doctors and nursing staff, psychology and pastoral care, have set out over several years to address these questions and find answers. The groups were advised by Mr. Pulheim, head of the Institute for Clinical Pastoral Care Training in Heidelberg.

These groups have tried to show alternative ways of dealing with the dying and the dead and have been inspired by both ancient and modern art.

During the seminars, the groups came across the art and pictures of the painter Ben Willikens. He deals with spaces in his paintings. The painter's pictures and his painted spaces create a "metaphysics" of space, in which and through which the experience, experiencing and enduring of death, mourning, letting go and the transitional situation of the dead find expression, remain in tension with each other and are not immediately given comfort or consolation and ready-made answers.

Jörg Hilfinger: Body Landscape, 1995, in the bay window room of the surgery department

Ben Willikens was prepared to implement the results of the in-house processes and transform them into the artistic design of a dignified mortuary space. The artist created something like a total work of art. From the suggestive light painting on the front wall to the design of the tap and the shelf for towels, everything was under his artistic direction. The room for the dead he created is intended to help relatives, doctors and hospital staff to say farewell to dead patients who have accompanied them as dying people. The room for the dead, inaugurated in 1997, is not open to the public.

In addition to art exhibitions, cultural events are held regularly. Three to four times a year, the Heart Centre invites patients to a music matinee, initiated and organized by the head senior physician Dr Bestehorn, himself a passionate musician. From time to time, the clinic also offers film screenings, such as Karl-Heinz Heilig's "Casa delle Favole" (House of Fairy Tales) two years ago. The author and filmmaker was of course present.

Mortuary

(Photo: Bechtel)

The work of art performs a different function in everyday hospital life than in a museum or gallery. It can probably be seen as a kind of catalyst or at least as an active companion in the healing process. Several aspects can be mentioned in this regard: Medical technology, which is often perceived as frightening by patients, is likely to be softened by the presence of art. What's more, the confrontation with the art object offers an alternative to the low-stimulus hospital routine. Patients who have been torn out of their familiar environment by their illness also suffer from the loss of a sense of security at home. Encounters with art may help to compensate for this withdrawal, as aesthetic perception helps to stabilize the patient's mental state. Overall, conversations about art, art contemplation or quiet art meditation may lead to an intensification of acceptance of personal fate. Sensitizing the senses through aesthetics also affects worried relatives as well as doctors and staff, whose workload - especially in emergency situations - is often extremely high. The inner dialog with a sculpture or a painting may calm emotional turmoil. Another message that curator Hill-Kalusche and Commercial Director Bernhard Grotz point out is the innovative aspect: Avant-garde, progressive art refers to the openness of the house and definitely also to progress in the medical field. Taken together, all of this probably gives the meaning and scope of "art in the clinic".

Mortuary

(Photo: Bechtel)

The essay by Dr. Ehrenfried Kluckert appeared in the April issue of Regio-Magazin.