Thomas Kitzinger

May 25 to July 4, 2008Hans Gercke, former director of the Heidelberger Kunstverein and an expert on Thomas Kitzinger's artistic work, has aptly characterized the artist's works with the term "dynamics of rigidity": "The sequence of motifs stripped of their context generates a new context in the presentation. Dynamics arise from rigidity, something like Brancusi's infinite column emerges from stacked cups."

Friezes of images take on an architectural quality; in a strange way, the artist contrasts the equally distanced treatment of a small number of highly diverse motifs.

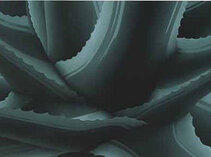

The monumental agave dominates the Attica corridor. You feel as if you could reach into the network of plants. The sublime photorealistic painting also owes its effect to the technique: oil on aluminum. Whether small or large format - the plant parts always appear enormous when cropped. In the series, they suddenly lose their floral character and are reduced to abstract, three-dimensional patterns. The dynamic tubular formations could represent microscopic structures that have been enlarged. The message could also be as follows: The further I penetrate into the microcosm, the more abstract and regular the patterns become.

Kitzinger's exhibited works date from the years 2003 to 2008.

Vita

- Born in 1955 in Neunkirchen/Saar.

- Awarded numerous prizes, including the Reinhold-Schneider Prize of the City of Freiburg in 2010.

- Scholarships offered residencies in Berlin, Paris and Stuttgart.

- Member of the Baden-Württemberg Artists' Association and the German Artists' Association, enabling numerous exhibitions in southwest Germany every year.

- Further exhibitions in Wiesbaden, Marburg, Kaiserslautern, Saarbrücken, Cologne, Berlin, Paris and Basel.

- Lives and works in Freiburg.

"Reality conceived as a shell": On the portraits by Thomas Kitzinger

Ehrenfried Kluckert

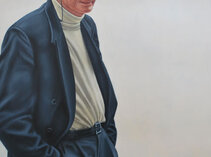

In the bright and wide passage leading from the rear entrance hall of the Heart Centre to the Roskamm House hangs a large-format painting by Thomas Kitzinger from 2008 depicting the founder of the Heart Centre, Professor Dr. Helmut Roskamm. The artist has painted a true and sympathetic portrait of the doctor. With a subtle smile, he looks over the edge of his glasses at the viewer. This is how patients, colleagues and staff may have experienced him and remember him today with a warm heart.

If you linger in front of the portrait for a long time, and this is not difficult, you may start to dream: At some point, perhaps on Christmas Eve between 12 o'clock and midnight, the professor steps out of the painting and puts his hand on your shoulder in a gesture of comfort - should you happen to be present ...

As I said, a dream image. Seen soberly, this visionary picture can probably only come into being because of its resolute realism. Super-realism, photo-realism?

The Roskamm portrait can only be understood from an artistic point of view if it is viewed in the context of Kitzinger's portrait art. Let's leave the "photo-realism" drawer open for the time being.

The "Dokumenta 5" of 1972 was held under the motto "Questioning Reality - Pictorial Worlds Today". Within this spectrum, "photographic realism" became acceptable in Europe for the first time. However, critics and theorists disputed the art status of a picture painted "as a photograph". What was the point of painting that simulated monumental color photographs? Gerhard Richter's thought contributed to the confusion and later clarification: "The photograph is not an aid to painting, but painting is an aid to a photograph produced with the means of painting.

"While painting had to assert itself against the new medium of photography about a hundred years earlier, photography was now invited into the artists' studios with a friendly gesture. Perhaps the idea that the subject of a picture is basically always a reflection of reality played a role here, whether abstract art, which assigned a reality of its own to the color form, or the realistic painting of past centuries. In fact, photorealism has given rise to a new variant: The picture not only depicts a photograph, but is identical with itself because it sees itself as a medium that has depicted itself in the photograph.

It remains to be seen whether a new academicism was born at that time according to the unfortunately still living principle: "Art comes from skill". Today we stand in front of Thomas Kitzinger's paintings and remember the motto of the 1972 Dokumenta: "Questioning reality". Indeed, the portraits, plant motifs and other objects are initially associated with photorealism and one would like to hastily construct a post-photorealism from this or speak flatly of "revival" or, even worse, of an "artistic retro look". That wouldn't be enough and doesn't get to the heart of the matter. In fact, the reality is up for debate.

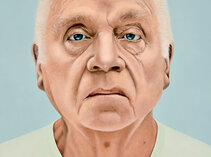

It's time to take a closer look at the portrait wall: "Aha, photorealism!" But appearances are deceptive. The picture titles reveal the deception: "10.3.53" or "26.8.32" and so on. Obviously, these are the dates of birth of the people depicted and not, one might add, a special code in which the person's characteristics and activities are encoded. The latter cannot be depicted either - or can it, in the pose, in the make-up, in the facial expressions peculiar to this person? But that is not to be seen, only what corresponds to the date of birth, i.e. what nature has given the person on the path of life, the form and shape of the physiognomy in the state of the picture's creation. The fact that a photograph served as a model here is irrelevant, as the people are from the artist's circle of friends and acquaintances and are therefore very familiar to him in terms of their appearance. The photograph merely provides a reminder of the structure of the facial structure in order to artistically translate the personality of the person.

Incidentally, it is interesting that Thomas Kitzinger has chosen a picture title that refers to the meaning of the picture, i.e. already provides an interpretation that leads to the heart of the matter. But what kind of core is it? Kitzinger removes so much from the reality of the faces until what appears is what nature has produced. So no pose, no facial expression, no emotion. The objection to this is that it is life that leaves traces on the face that help to shape the specific type of person. We can agree with this by pointing out that these are traces in the trajectories of the physiognomy predetermined by nature.

This decisive reduction of the phenomenon "face in the state of its everyday experiential space" leads to the essence of natural physiognomy without all the socially and culturally influenced world.

This artistic process can be compared with the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, who at the beginning of the last century spoke of a "phenomenological reduction", which leads him to the "it-self", to the essence of a phenomenon: Everything we know about an object, every emotion that we associate with the object and every external imprint that an object has experienced, we must push aside in order to grasp the essence of this object.

While working on the painting, however, Kitzinger stops where Husserl continues to pursue his philosophy of the "It-self" and becomes entangled in it. He postulates an "ego without a world" in order to advance to "pure consciousness". However, a worldless ego deprives "pure consciousness" of the object for which it is supposed to take up the work of seeing, perceiving and recognizing. The ego is always a subject for the world and at the same time an object in the world - a paradox that Husserl was unable to resolve.

Kitzinger did not read Edmund Husserl's "Idea of Phenomenology", but he read Marcel Proust with passion, who, like Husserl, wanted to get to the bottom of events, people and phenomena, but first and foremost wanted to get to know himself down to the deepest depths of his soul. On the first pages of "Swann's World" ("In Search of Lost Time"), he lists his sensations in the gray zone between sleeping and waking and the illusions of the dream images that arise after he wakes up and make him believe in an illusory reality. In this enumeration, he exposes himself in order to get to know his own self.

The comparison with Husserl's "Phenomenology" is intended to be nothing more than an explanatory model for Kitzinger's artistic project. The essence of a face consists in the physiognomy predetermined by genes and shaped by nature. This is in line with the artist's idea, who characterizes his pictorial objects as "reality conceived as a shell". And this applies not only to Kitzinger's "birth date portraits", but also to his objects such as balloons, plants, vases and other objects.