Peter Stobbe

Vita

"If models are something existing on a small scale or something future, such as the model of a house to be built, then photographs are small-scale models of existing objects."

This idea from Peter Stobbe's "Dingstudien. An attempt at a theory of visuality", which has been in preparation since 2001, appears surprisingly simple, but turns out to be a precise miniature system in the best tradition of Ludwig Wittgenstein's thinking. Both share the simple form of far-reaching thought models. When Wittgenstein points out in his Philosophical Investigations that "every sentence is a complex of names corresponding to a complex of elements", he presents a sound model of interpretation for every kind of work of art. The description of a painting - provided we succeed in describing it in one sentence - contains the elements of the painting such as compositional elements, motifs, coloration, perspectivity or other pictorial means as a complex system. It is then only a matter of combining the artistic means to create complexity, in other words, to be able to read the "pictorial text".

How is that possible? In a non-objective picture whose "sentence" I have deciphered, I arrange the elements into a pattern that corresponds to my need for beauty - or not. My aesthetic judgment will turn out accordingly. The parallel with Stobbe's thoughts is obvious. If we replace the terms "models" with "pictures" and "photos" with "picture motifs", the coherence of the system becomes apparent: picture motifs do indeed refer to existing objects. This statement need not be in contradiction to abstract painting, insofar as the color bar or the graphic hatching must be ascribed its own aesthetic reality or objectivity - in accordance with the "autonomy of artistic expressions".

Of course, pictorial motifs are only valid as motifs of a picture that refer to a certain area of reality or assert a reality of their own. This context is revealed to me by searching for and arranging the inscribed pictorial motifs. I finally arrive at my complex pattern, read it and decide whether it has a pleasant or unpleasant effect on my senses ...

Voilà! That brings us back to Wittgenstein!

I am aware that this theoretical digression is exhausting. But without it, we would not be able to approach the person and work of Peter Stobbe. It would be like trying to look at the fish without thinking about the water ...

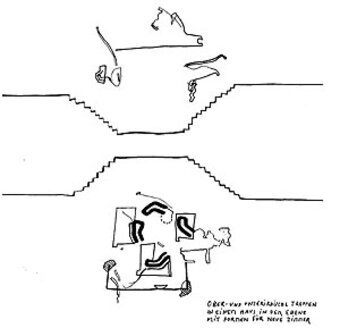

Stairs above and below ground in a house on the level with molds for new rooms

Peter Stobbe's artistic activity unfolds in a force field of theory, poetry and artistic work. Let's start with his dazzling educational background. Born in Büdingen, Hesse, in 1951, Stobbe studied psychology and philosophy as well as Slavic, English and linguistics at the Justus Liebig University in Giessen. In 1980, he completed his doctorate on Velimir Chlebnikov at the Albert-Ludwigs-University in Freiburg im Breisgau. In 1981 he began working as an artist and writer, received two scholarships from the Baden-Württemberg Art Foundation and in 1988 took up a guest professorship at the University of Wuppertal in the Department of Communication Design, replacing Professors Siegfried Maser and Bazon Brock. He has been teaching at the Lucerne School of Art and Design since 1990. He was awarded the title of professor in 2001.

Among his numerous publications, the "Baubuch. Die Fliegenden Häuser" from 1988 and "Nach Delft gehen" from 2001. The texts are both lyrical and dissecting. Many passages in the "Delft Book" are touching; others surprise with their lyrical tone or precise powers of observation: "The sand on the square in front of the Oude Kerk looks as if someone had just raked it. Not even the imprint of a cat's paw can be seen, not a scrap of paper, not a lost item of clothing and not a dead bird."

Stobbe has chosen Hieronymus Bosch's "Tramp" to accompany him to Delft. He calls him Landlooper: "There's a party in Mechelen tonight, he says. People from another time are coming."

It is the painters Vermeer, El Greco, Andy Warhol and others who present themselves to the Landlooper's artistic cosmos, if you will, to Hieronymus Bosch's eye.

The book is easy to read, you feel as if you are floating in history. Nevertheless, or perhaps precisely because of this, the author has taken an incomparable philosophical flight of fancy. The book has 124 pages - not including the many hundreds of pages that can be calculated from the interlineations...

In "Baubuch", archaic thoughts circulate about the meaning and function - to put it bluntly - of housing: "New rooms. They serve other purposes, which ones? The room protects the individual from the rigors of the weather. It is equipped with the communication forms of the far-reaching ear and the far-reaching mouth, as well as the circumstance of the centered eye."

Sketches, which certainly have their own artistic value, explain the statements. The acoustics and visual availability of a room take center stage and are presented as the basis of living. One could almost say that human sensations, concretized in the modes of reception and articulation of perception, represent a kind of pre-furnishing of the New Rooms - perhaps also a final one.

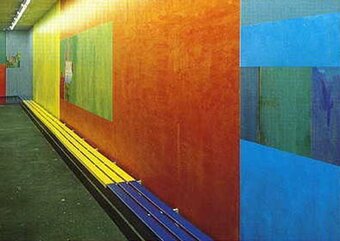

Stobbe's thoughts contain pictorial material and are aimed at design. In the context of his theory and poetry, his wall installations and paintings in the dining room of the Heart Center appear as icons of a comprehensive spatial experience. They are not just "pictures on the wall", but an artistic catalyst to intensify the perception of space: I can only see the works in the context of the columns, tables and chairs. This static component is softened: the people in the room, busy with their painting or with their conversation partners, leave behind "traces of movement", which I find again in the structure of the paintings. What's more, the mood of the room may unfold in the contrast between small-scale and large-scale objects, chiseled hatching, material elements or sublimely colored surfaces. The effect on the viewers, the heart patients and their relatives as well as the hospital staff, is certainly not absent. The ensemble has an effect on the emotions of the people in the room, who can redefine themselves on the spot - even if it means that they are momentarily removed from everyday hospital life, their illness and the fears associated with it.

It is possible that Peter Stobbe pursued a similar concept together with Hansjürg Buchmeier in August 2002. The project involved the design of a passageway between two wings of a school building in the Berghof complex in Wolhusen near Lucerne. The result is a new way of developing a personal sense of space. The atmosphere does not result from the color treatment of the walls - which is the obligatory coloristic basis - but from the interlinking of image and text. The miniature wall words such as "Lichtbank", "Zahlenstau" or "Heftdienst" seem to hide in the expanse of the color surface - but they are impossible to overlook and set the color in motion like a small aesthetic generator. The words draw the eye to themselves and at the same time to the differentiated treatment of the wall section. Traces of guttering and changing transparency of the colors, iconic fragments and painterly breaks from the linearized direttissima catch the eye. Pupils passing by identify with the text and learn - quite incidentally - to decipher the color code and the icons encoded in it, so that they are soon able to develop a personal sense of space.

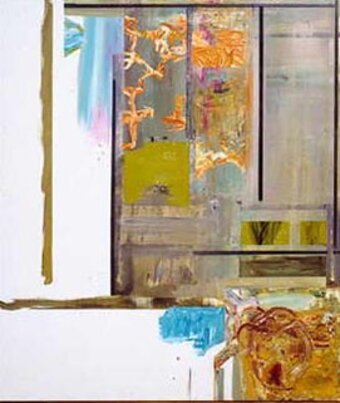

Apart from the latter project, the works in the Heart Center date from 1990 and 1991. What has happened in the Stobbe studio since then? Let's take a look at the contrast calculation of the dining room installations. A large-format two-part work entitled "Recognizing the picture by its fingers" dates from 1998. It consists of two panels of equal size, one monochrome, the other colored. In a way, you are invited to "look in between", to color the monochrome figuration and reduce the color composition. The work functions as a mirror of my perception: in order to see the picture, I have to "paint" it with my eyes! Or to put it another way: the canvas is not the painting surface, but the retina of my eye. "Bildwerk I" from 1999 works in a similar way, a large-format work that provokes spaces in its pictorial structure. The strict parallelism of the lines borders abruptly on a dark ground, which bears a compact and only slightly structured form. It is actually this expansive pictorial detail that we feel compelled to look at, but our eyes are repeatedly drawn away and towards the striped edges. Visualizing this interlocking abstract double portrait is difficult at first. But once we have engaged with the artistic rhetoric, we feel that we are about to experience the grammar of a new visual language. It is worth doing this visual work because, equipped with a new perceptual code, we can not only "read" the latest works, but also appreciate them to the highest degree.

Bildwerk I, lacquer and acrylic on wood, 230x160 cm, 1999

Japanese hut, oil on canvas, 140x120 cm, 2001

The "Japanese Hut" presents itself to the eye like a three-star menu: The clear bar structure sets the mood for the feast. You can't wait to stroke the monochrome surfaces, which look like they're made of velvet, and let the golden-brown pieces melt in your mouth ... A feast for the eyes! Stobbe is a master of synaesthesia. For him, the visualization of the aesthetic material reveals itself in the activation of further sensory perceptions: The eye stimulates the palate and awakens desires in the fingertips.

Perhaps this is why the "Kunstsätze" were created. These are spoken texts, short and concise sentences that were produced as a CD together with Hansjürg Buchmeier in 2002. The spoken word acts and animates the thought. As an acoustic signal, it finds direct access to the consciousness without being filtered through a written image. The message is clear: if it is possible to "read" a picture, why not "hear" it? The visual signs of an iconographic code can also be perceived acoustically.Peter Stobbe's iconography, the symbolic, allegorical or metaphorical pictorial signs, are systematized in his "Theory of Visuality" (2002), which is currently in progress. Among other things, this involves a differentiation of the creative process. As paradoxical as it may sound, the differences between text and image give rise to similarities: "Writing is more confusing than painting. You are quickly in the "picture" when you look at a painting. This is not possible with longer texts. Reception works differently. A longer text has something of the burrowing work of the blind mole. You have to somehow "fight your way through", it takes longer than looking at pictures, although a text, I think at the moment, is also a kind of painting, only applied with a very small brush, which requires a lot of patience. I've always found painting, at least my painting, to be very impatient. I could hardly wait until the painting was finally finished. With writing, I now have to learn the density of painting in order to stretch out sentences, sections and chapters."